Introduction: More Than Just a Buzzword

Over the last decade, toxic masculinity has shifted from a niche academic concept to a mainstream talking point. It has been discussed in political debates, dissected in think pieces, and weaponised in social media discourse. Yet beyond the cultural tug-of-war over the term’s meaning, one fact remains clear: toxic masculinity is costly — emotionally, socially, and economically.

A landmark study by Promundo and Axe estimated that harmful masculine norms cost the United States at least $15.7 billion annually in direct and indirect impacts, from violence and untreated mental illness to lost workplace productivity. That figure only accounts for men aged 18 to 30 and a limited set of outcomes, meaning the true global cost is almost certainly much higher.

But the most damaging effects aren’t reflected in financial spreadsheets. Toxic masculinity erodes relationships, mental health, and life potential. And while it unquestionably harms women and marginalised groups, its effects on men themselves are often overlooked.

[Image Placeholder: Infographic showing the $15.7 billion annual cost breakdown from the Promundo/Axe study]

What We Mean by “Toxic Masculinity”

The term doesn’t mean that masculinity itself is inherently bad. Rather, it refers to a rigid, culturally constructed set of expectations about what it means to be a “real man.”

Sociologist Michael Flood describes these expectations as emphasising dominance, aggression, stoicism, and control — while devaluing vulnerability, empathy, and collaboration. The so-called “Man Box” identified by Promundo outlines seven common traits associated with these norms:

- Self-sufficiency at all costs

- Physical toughness

- Sexual dominance

- Aggression to resolve conflict

- Rejection of anything “feminine”

- Strict adherence to heterosexual norms

- Suppression of emotions

While some traits like resilience or ambition can be positive in moderation, when enforced rigidly they can lead to self-destructive behaviours. And because these norms are socially rewarded — through peer approval, workplace advancement, or perceived romantic success — many men internalise them without question.

The Emotional Toll: Men Behind Emotional Walls

From early childhood, many boys are taught that crying is weakness, that seeking help is shameful, and that vulnerability will be punished. This conditioning creates emotional illiteracy — the inability or unwillingness to recognise, name, and process emotions.

Psychologists note that suppressed feelings don’t vanish; they resurface as anger, cynicism, substance abuse, or withdrawal. Over time, these coping mechanisms damage not only personal relationships but also a man’s own sense of identity.

Research consistently links adherence to traditional masculine norms with:

- Higher rates of depression

- Reluctance to seek therapy

- Greater likelihood of self-medicating with alcohol or drugs

- Increased risk of suicide (men make up around 75% of suicide deaths in countries like Australia, the UK, and the US)

As Gary Barker, CEO of Promundo, notes:

“When guys believe they need to be tough, not ask for help, and seem cool at all costs, the consequences go far beyond rudeness or telling a sexist joke — they can be fatal.”

Economic Consequences: The Billion-Dollar Price Tag

While the emotional cost is profound, the financial toll of toxic masculinity is both measurable and alarming.

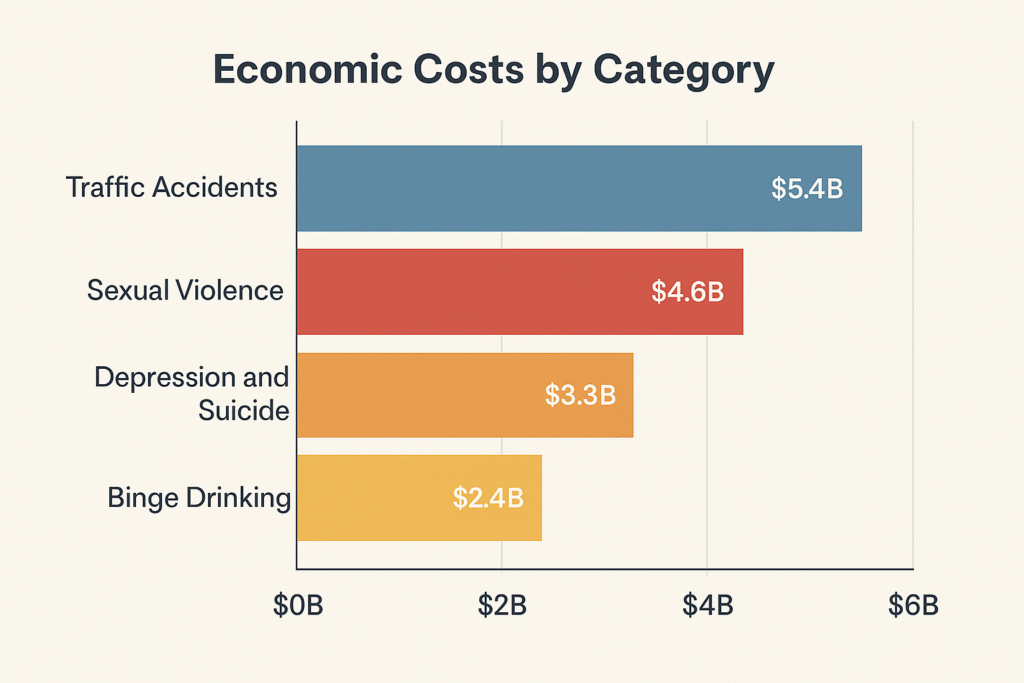

The Promundo/Axe report calculated costs in five main areas for men aged 18–30 in the US:

- Violence – Costs from sexual assault, physical fights, and bullying.

- Traffic accidents – Men’s higher likelihood of engaging in reckless driving.

- Depression and suicide – Lost productivity and healthcare expenses.

- Binge drinking – Medical treatment and workplace absenteeism.

- Bullying – Educational disruption and future earning impacts.

These costs stem from behaviours rooted in proving toughness, dominance, or risk-taking — all hallmarks of rigid masculinity.

And this is just the “bare minimum” estimate. The study did not include older men, other forms of violence, or the hidden economic value of emotional wellbeing. In reality, the true price is likely several times higher.

[

The Social Costs: Broken Relationships and Limited Bonds

Toxic masculinity erodes men’s ability to form deep, supportive connections. The constant pressure to compete rather than collaborate often breeds isolation. Friendships become shallow, emotional needs go unmet, and romantic relationships may suffer from communication breakdowns.

Michael Flood warns that this isolation has a ripple effect: men who lack strong support networks are more vulnerable to mental health crises, substance abuse, and extreme behaviours. Meanwhile, their partners, children, and friends bear the secondary emotional costs of these struggles.

Over time, the inability to express vulnerability limits men’s capacity for genuine intimacy — not just with others, but with themselves.

[Image Placeholder: Two men shaking hands formally instead of hugging]

The Health Impacts: Dying to Prove Manhood

Rigid masculine norms also show up in men’s physical health statistics:

- Men are less likely to seek preventive medical care.

- They have higher rates of substance abuse.

- They are more likely to die in workplace accidents due to risk-taking behaviour.

Even fitness culture isn’t immune. While healthy exercise is beneficial, the obsession with muscularity — often driven by insecurity rather than wellbeing — can lead to steroid abuse, eating disorders, and injury.

In essence, the “invincibility” myth is killing men.

Why “Toxic Masculinity” Sparks Backlash

Some critics argue the term unfairly shames men, or that it’s an attack on masculinity itself. Feminist scholars counter that the issue isn’t being male, but the harmful version of masculinity that society overvalues.

Flood acknowledges that the negative framing can trigger defensiveness:

“Because the term contains such a negative descriptor, it’s easy for men to dismiss it as something that doesn’t apply to them — even when it does.”

However, avoiding the term entirely risks losing a powerful tool for raising awareness. The key is to balance critique with a vision for what healthier masculinity can look like.

Intersectionality: Not All Masculinities Are the Same

Toxic masculinity doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It intersects with race, class, sexuality, and culture — meaning its expression and impact vary widely.

For example:

- In some communities, economic marginalisation may intensify pressure on men to assert dominance as a form of self-worth.

- In LGBTQ+ contexts, toxic masculinity can manifest as internalised homophobia or hypermasculine posturing to “pass” in heteronormative environments.

Recognising these nuances is essential for designing effective interventions. One-size-fits-all approaches risk alienating the very men they aim to reach.

Towards Liberation: Rewriting the Script

Challenging toxic masculinity is not about erasing masculinity, but broadening the definition. Men can be strong and gentle, ambitious and empathetic, competitive and collaborative.

Practical strategies include:

- Early education – Teaching emotional literacy and dismantling gender stereotypes in schools.

- Role modelling – Highlighting men who embody compassion, humility, and integrity.

- Therapeutic spaces – Making mental health care accessible and stigma-free for men.

- Peer accountability – Encouraging men to call out harmful behaviours within their circles.

As Jaclyn Friedman writes, a reinvented masculinity will give men “more room to express and explore themselves without shame or fear.” The goal is not to strip away identity, but to liberate men from a cage they didn’t build, yet still live inside.

Conclusion: Counting the Real Cost

Yes, the economic cost of toxic masculinity is staggering — billions lost to violence, health crises, and missed potential. But the deeper loss is immeasurable: the friendships never formed, the emotions never expressed, the help never sought.

By dismantling the harmful norms of masculinity, we don’t just create safer spaces for women and marginalised groups — we free men themselves from a damaging, limiting script. The dividend is a society where men can be whole humans, not performance pieces in a gendered play.